“Orpheus is the great musician of antiquity”

January 21, 2019 Articles

BY KIYA VAN DER LINDEN-KIAN

Separated from the love of his life Eurydice, Orpheus vows to descend into the underworld and win her back. But, just before they are both freed, he turns back to look – a move that sees his love lost forever…

From Berlioz’s Les Troyens to Scriabin’s Prometheus,ancient Greek myths – with their epic themes, tragic love stories, and comic routines – have inspired many settings in classical music.

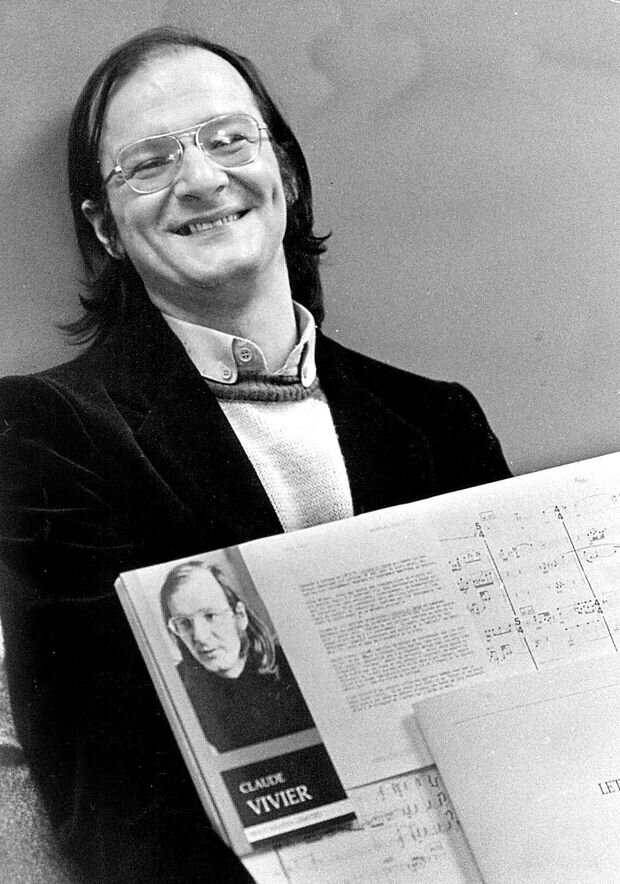

Of all of these myths, few in the canon are as compelling as that of Orpheus. Both Monteverdi and Gluck wrote operas based on the musician hero, but now composer Evan Lawson has written his take on the classic myth – or, as he calls Orpheus, “the great musician of antiquity”.

Forest Collective composer Evan Lawson captured by Karin Locke.

Evan has been at the helm of the Forest Collective since its inception in 2009. He has been enticed by Greek mythology before, writing an opera on the story of Calypso and Odysseus in 2013. And now, he wants to retell the Orpheus myth and empower “the voices of characters generally disadvantaged” in the story. Evan’s Orpheus focuses on the lesser-known queer relationships in the myth, and tells some of the lesser-known details of the legendary tale.

With all things considered, this isn’t your average opera. In fact, it’s not even an opera! Orpheus is ballet-opera, which is built around danced and sung passages. The collaboration is undertaken with dancer Ashley Dougan.

Evan wants to flip the script on the story and let the audience see the events from another perspective. I had a chat with Evan about the direction of Orpheus, and what inspired him to write a ballet-opera in the first place.

Hi Evan, thanks for chatting with us. What compelled you to retell the Orpheus myth, and what do you think has inspired its many settings in music?

Orpheus is the great musician of antiquity. He was meant to have been the most beautiful lyre player and singer of the ancient Greek recitations, so that in itself lends itself easily to musical dramatisation. It’s also a damn good story, especially the section where he goes to the underworld. Not only does he survive this huge task, but the interaction with Eurydice is sad, beautiful, and poignant – the idea that he was so overcome with emotion, love, and anxiety that he did what he was told not to do, and turned around and lost her forever.

I wanted to retell this well-known myth because there is an unknown aspect of it in the relationship with Calais, an adolescent man who Orpheus had a pederasty relationship with. This sort of relationship is common to ancient Greek myth and culture in-general, where an older man has a mentor-type sexual relationship with an adolescent man. We often know these myths through Victorian versions that eliminate any same sex relationships.

Aside from that, most of my music focuses on ancient Greek myth and tradition, as I find it an ever-inspiring source of musical and social ideas, most of which are the building blocks of contemporary Western art and thought.

LGBTQIA+ relationships and characters can often be found throughout Greek myth. What made you decide to focus on the relationship between Orpheus and Calais specifically?

It added an interesting complexity to the relationship with Eurydice. In the versions I could find, it was clear he loved Calais while on the Argo with him. In the opera, we open with Orpheus saving his life, and the other Argonauts, from the lure of the Sirens. Orpheus and Calais sing a love duet and enjoy their love for each other.

After this episode, in all the versions I found, there was nothing about how he met Eurydice or of what happened to Calais: he simply went on to marry Eurydice and then she died, which leads to the famous cave sequence. I decided to use this lack of information to focus more on the pawns of the story, Calais and Eurydice, and show how the story is always geared toward the hero, leaving these often distraught characters in their wake.

So, the Orpheus and Calais relationship is given focus, but so is Eurydice as a strong woman, made to suffer and die for the sake of a male hero.

This is your second opera, and your first was about Calypso and Odysseus. What draws you to telling the stories of ancient Greek myth and can we expect to see any overlap between the two works?

In Calypso and Odysseus, it was a very similar situation; Calypso is almost an afterthought in the Odyssey. She’s hardly given one page, but Odysseus stays on her island for something like seven years! And she’s portrayed as the scheming, lustful woman, so I wanted to right that wrong. The man had a wife and kids back home, but it was okay for him to stay in her kingdom and for him to be taken advantage of…

I understand the libretto is a combination of Monteverdi and Gluck’s libretti of their respective Orpheus operas. What were some of the challenges in putting these two stylistically different artists together?

It was from a desire to take the voices of characters generally disadvantaged in opera historically (women, mainly, but also in this instance the ‘gay’ man Calais), and take those words and try to empower these characters, rather than disadvantage them as they generally are in the older works.

I’m very aware of being a white man who is creating female characters and making them go through horrific things. In this version, Eurydice’s death and the journey of her soul from body to Hades is depicted quite graphically. This is the norm in opera – with men making female characters go through pain – and I wanted to try and empower the female character and performer to show a more genuine and human side, less dependent on the actions of a heroic man; and, also, just to acknowledge the fact that I am a man asking a female performer to portray this.

The libretto also contains words from Phemocles, a lesser-known Greek writer of prose and poetry, and a section from a Shakespeare sonnet.

How did you decide to make the work a ballet opera? What draws you to the format?

Opera isn’t a new form for me: I’ve already had one performed, and used to write many while I was in high school. Dance is a form that I love, but had never worked in. So once the opportunity arose to work with the amazing Ashley Dougan, I thought of the Orpheus project.

My initial conception of the work was for it to be a cross-genre symphony-opera, so it seemed logical to take another genre-bending step and include dance into that, too.

The form, ballet-opera, is one that seems new to us now, and is common with many contemporary composers. However, in the works of Gluck, Lully, and the operas of the French empire, dance was a very common aspect to an operatic production, so there is a canon to draw on.

What are some of the key messages of the Orpheus myth that audiences will take away for your work?

I hope the audience will take away an ease in seeing two men declare their love to each other through song. But also, within an opera context, be confronted by the true pain of a woman and how we allow these characters – crafted by men but portrayed by women – to live on stage.

Ashley Dougan captured by Meghan Scerri.

See the Forest Collective present Orpheus as part of Midsumma Festival and Convent Live, January 31-February 3. The work is supported by Creative Victoria and City of Yarra and is a co-commission between Forest Collective and Prismatx Ensemble.